PLASTIK, and other man-made marine hazards

My art series, "Plastik," was born out of a realization about the impact our daily actions have on the environment. When I first saw the "No Dumping, Drains to Ocean" signs, I began to connect the dots between our littering, spilling, and the pollution that eventually finds its way into our oceans through city storm drains. With this series, I aim to shed light on the direct consequences of our choices and actions, emphasizing our responsibility within the larger environmental picture.

Through my art, I illustrate the implications of plastic waste and overuse on our planet, particularly on our oceans. By using various visual elements and techniques, I hope to engage the viewer and encourage them to reflect on their role in the preservation of our environment.

Ultimately, "Plastik" is a reminder that our actions have a lasting impact on the world around us. By acknowledging the dangers of plastic waste and pollution, we can take steps towards a more sustainable future and a healthier planet.

All photographs presented here are the sole property of the artist unless otherwise noted. Published works are protected under domestic and international copyright laws and are not considered to be public domain. None of the photographs may be reproduced, copied, manipulated, or used whole or in part of a derivative work, without written permission. All rights reserved.

No Dumping, Drains to Ocean

Eighty percent of pollution to the marine environment comes from the land. The storm drain is the drain found outside your home or business. Those are the drain inlets or catch basins you see at the end of the street/gutter. They are stenciled with the sign shown in the photo. They covey rainwater directly to the ocean and bay, untreated. That's why it is so important to prevent anything but rain from entering the storm drain. (Photograph: Sabine Pearlman)

Ingested Plastic Pieces

These are plastic pieces found inside the stomachs of young albatross birds. Each photograph represents the bolus contents of one bird. The parents had picked up these plastic pieces accidentally while traveling thousands of miles over the surface of the ocean searching for food to feed their chicks. Unfortunately they were not able to distinguish between what's organic and eatable and what isn't. When birds fill up on large amounts of indigestible matter they'll starve to death as nutritious food can no longer enter their system.

(Photographs: Sabine Pearlman | Specimen: courtesy of Algalita Marine Research and Education)

Fishing Line

This fishing or monofilament line came from the stomach of an adult albatross. It was probably mistaken for strands of squid eggs or fish eggs, which are part of the natural diet of these birds. Fishing line is wound into tight wads inside the stomach and is not easily purged from bird, leaving little room for food to pass through its system. Many birds are therefore left starving to death through the consequences of plastic pollution. (Photograph: Sabine Pearlman | Specimen: courtesy of Algalita Marine Research and Education)

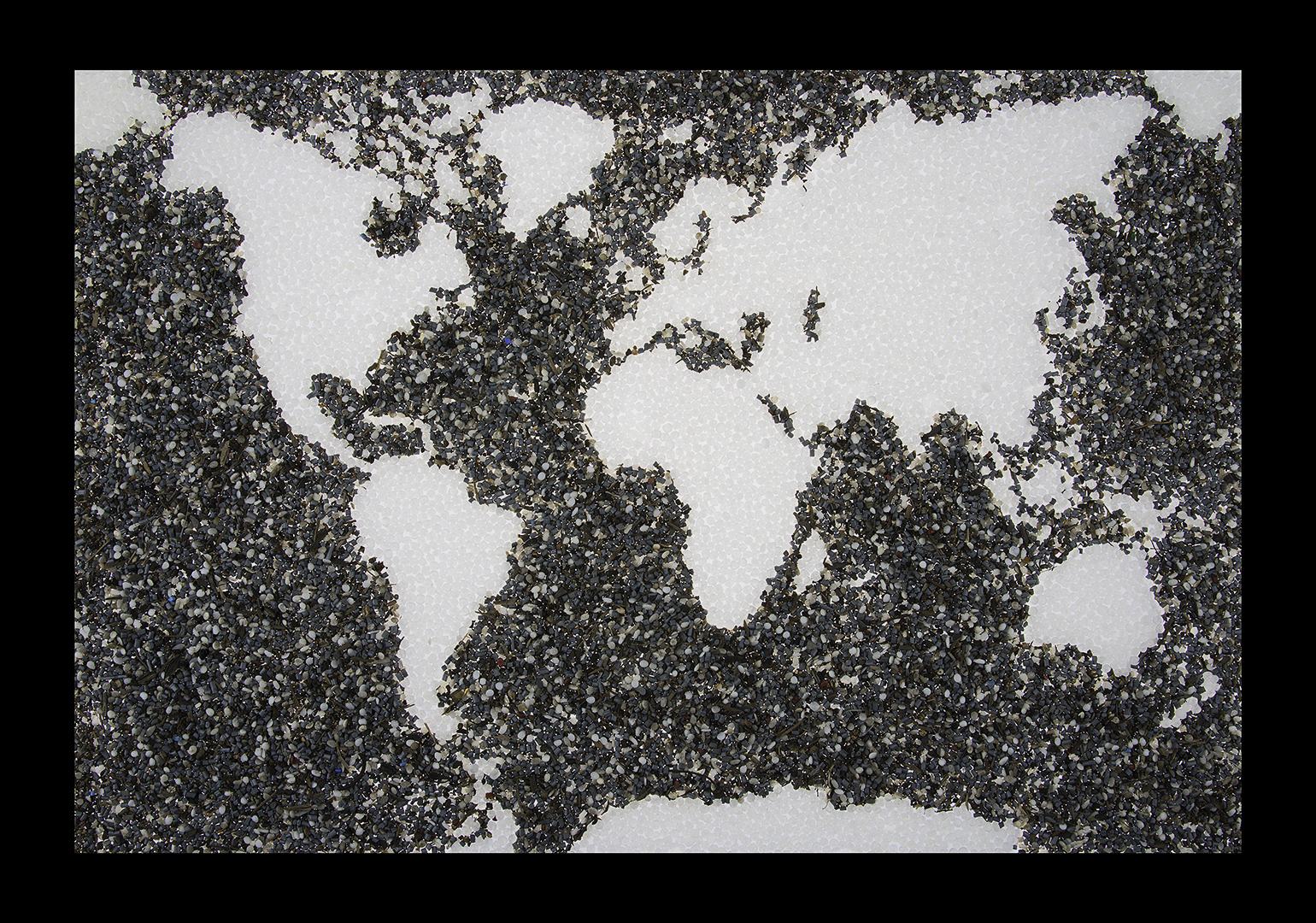

Plastic Nurdle World Map

A large portion of marine debris consists of plastic nurdles. Nurdles, or pre-production plastic pellets can be found on beaches all over the world, including the arctic, making them one of the biggest threats facing ocean life today. Many of the pellets are lost either during transport from the plastic manufacturer to the processors, or through poor housekeeping practices at the processing facilities. Some nurdles are not processed but are used as stuffing for “beanie” toys and other items. (Photograph: Sabine Pearlman | Specimen: courtesy of Algalita Marine Research and Education)

Dense Foam

Recent research illustrates that plastic debris in smaller sizes is becoming more prevalent in the ocean, due partially to photodegraded pieces of plastic that are breaking down but not going away. Plastic is a mix of monomers linked together to become polymers, to which additional chemicals can be added for suppleness, flame resistance, and other qualities. Because of their properties, plastics are essentially “forever”: they do not biodegrade or dissolve into organic matter that can reenter the life cycle. Instead plastic photodegrades, which means, it breaks up into smaller pieces when exposed to sunlight, and these smaller pieces persist in the marine environment for hundreds of years. (Photograph: Sabine Pearlman | Specimen and source: courtesy of Algalita Marine Research and Education)

Foam Packaging

Fragment of molded foam egg carton. Expanded foam such as this is used for a variety of types of food packaging, take-out containers, and food service items (bowls, plates, and cups). These are all single use items. Expanded foam is also used extensively in packaging and shipping. This type of foam is a very common debris type found during beach cleanups. (Photograph: Sabine Pearlman | Specimen: courtesy of Algalita Marine Research and Education)

Walk on the Beach

Plastic fragments found while taking a walk on the beach. These items represent a safety and health hazard to us and the marine animals.

Fishing Hooks

These hooks are part of a commercial fishing activity called long-line fishing. They are baited and trailed on a line behind a fishing vessel to attract and catch fish from below, but if a bird spots the bait from above and dives on it, it can also be caught on the hook and drown. (Photograph: Sabine Pearlman | Specimen: courtesy of Algalita Marine Research and Education)

Float

Floats come in all sizes and shapes. All floats are designed to keep things suspended near the surface of the water. This is small fishing float, other floats may be 6 feet or larger. When floats are used for their designed purpose they are good, but when they become debris they can cause harm or create dangerous situations in the environment, such as, some small floats have been ingested by animals, some animals may become entangled in the line attached to the floats, and larger unattached free floating floats can pose a hazard to navigation. (Photograph: Sabine Pearlman | Specimen: courtesy of Algalita Marine Research and Education)